I hope that Beatles reference was funny, but this next topic is not. it definitely is interesting, but cancer is never funny. That being said, I do like to have entertaining blog post titles 🙂

This next study we’re looking at is very interesting and actually close to my heart. I’ve done my fairshare of work in this! My MSc was looking at dysfunctional G2 decatenation checkpoints in breast cancer. Dr Tanya Soliman, one of the authors of this post’s study, was my project supervisor. This paper formed a cornerstone in my project! Working with her all-woman team was fantastic; amazing to be surrounded by such smart and dedicated women working mostly on ovarian cancer while I was looking at breast cancer. Both are detrimental to women, it was an honour to work on this with other women, especially as my aunt died from breast cancer as well.

Now then, lets look at the details. What is PKCe and what is Topo2a? Let’s go to the basics first before covering this.

IMAGE: A brightfield microscopy image taken from my own mitotic trap assay work on breast cancer cell lines. I want to say this is MCF10aCa1a, but I can’t remember!

The Cycle Of (Cellular) Life

Cells undergo a regulated series of events to form two new identical cells, collectively referred to as the cell cycle. There are multiple steps: G1 phase, S phase, G2 phase, and Mitosis. Throughout the cell cycle are multiple checkpoints consisting of many regulatory pathways. These checkpoints ensure that cells have undergone the duplication of cellular material and DNA with no mistakes. The regulation of the cell cycle is essential for proliferation of healthy cells, otherwise serious issues can arise, like cancer.

Checkpoints Ahead…

The cell cycle is regulated via four main checkpoints: the G1 checkpoint (also known as S phase restriction point), the S phase replication checkpoint, the G2/M phase checkpoint, and the mitotic (spindle assembly) checkpoint. Before each checkpoint, certain conditions need to be reached to proceed to the next part of the cycle. The G1/S phase checkpoint occurs just before S phase starts; the cell needs to be large enough in size. For the cell to be large enough in size, there needs to be more volume of the cytoplasm fluid, enough cytoskeletal machinery, and cell components. The size of the cell is important in regulating the cell cycle length; if the cell size is not large enough, G1 will be delayed so that the cell can grow large enough in size for the next phase. A study demonstrated this idea of cell size dependency in the cell cycle; it was found that larger daughter cells were able to progress faster in the cell cycle than smaller daughter cells (Killander & Zetterberg, 1965; Barnum & O’Connell, 2014). Another study by Fantes in 1977 supported this relationship between cell size and cell cycle time found in Killander & Zetterberg’s study (Fantes, 1977; Barnum & O’Connell, 2014).

The G2/M checkpoint occurs after the DNA has been replicated in S phase. At this point in time, the cell has 2 copies of its full genome. During replication, the DNA strand opens to form a replication fork and allows replication to occur; in this process, the DNA on either side of the fork will become catenated (tangled). The next checkpoint is to ensure that the DNA is coiled correctly after replication; the cell must check whether there are still tangles present or if there is any DNA damage or mistakes made. If there are mistakes made, the cell will undergo cell cycle arrest and delay mitosis to repair the damage and prevent any serious issues.

Lastly, the conditions to meet the mitotic checkpoint is that the spindle fibres are attached to the sister chromatids during metaphase correctly from both poles so that anaphase can begin (Barnum & O’Connell, 2014).

G2 Decatenation Checkpoint

We discussed the DNA Damage Repair Pathways previously in my other post (click here to read it if you haven’t already, I’ll wait for you here while you do). These are involved in G2, however, there is a separate checkpoint in G2 called the G2 decatenation checkpoint. This is where our focus will be.

In addition to, and distinct from the DNA Damage induced G2/M checkpoint is the Topoisomerase 2a dependent checkpoint. Topoisomerase 2a (Topo2a) is particularly significant; this is an enzyme that is responsible for fixing catenated DNA by forming double-stranded breaks and letting the strand move through in order to rectify the structure.

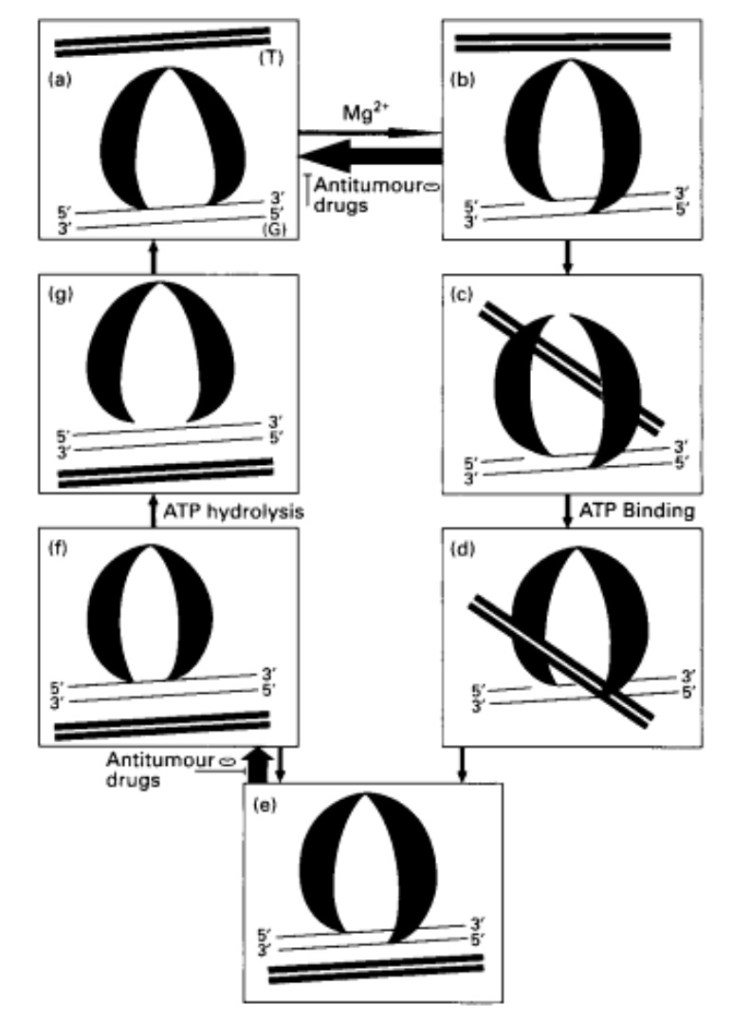

DNA tangles during replication, as the coil is opened to allow the replication machinery to read the leading strand and to synthesise a new strand, as part of the semi-conservative nature of DNA. This can lead to tangling and winding-up of the DNA on either side of the replication fork. To ensure that the DNA is coiled correctly with no tangles after replication occurs, Topo2a creates a double-stranded break where the tangle is and recognises where there is entanglement; it allows the strands to move through each other and to coil correctly in an ATP-dependent process. The Topo2a creates a gate to allow the tangled DNA to separate and detangle. This then allows the DNA to untangle and join once correctly oriented (Figure 1) (Watt & Hickson, 1994; Knoop et al., 2005). If the DNA is not adequately untangled prior to entry to mitosis, a checkpoint is initiated at the G2/M boundary. The G2/M checkpoint is especially important in this discussion, as p53 regulates this process of checking the DNA. p53 is a transcription factor and a tumour suppressor and is significant for cell cycle arrest. The combination of the activity of p53 and Topo2a is essential for regulating the DNA and checking that it is not damaged for mitosis to occur.

Lockwood et al.‘s 2022 Study

Now we get to the main study, where we’ll lay out each finding from this paper and how it relates to what we already know about the G2 decatenation checkpoint.

Resistance in cancer and the inability to die despite patients suffering through chemotherapy is not new, but we scientists are still uncovering the mechanisms of why this is. One of these reasons is that there is a dysfunctional G2 decatenation checkpoint; some research (including my own) show that some cancers do not arrest when reaching the G2 decatenation checkpoint with catenated DNA. Therefore, in cancer cells an alternative pathway is required to continue in the cell cycle.

As you may know, p53 is a tumour suppressor essential in the regulation of all sorts of processes from cell replication, the cell cycle, all the way to apoptosis. The researchers therefore wanted to examine the fidelity of the G2 decatenation checkpoint in p53-wild type (WT) and p53-mutant cancer. To do this, they used topo2a inhibitors (an example is ICRF193, which I’ve used) on p53 WT and mutant cell lines. The reason for this is that the DNA would not be able to be decatenated by Topo2a (which was inhibited) so the cells were unable to proceed; the checkpoint was activated. When mutant p53 cell lines were given the same treatment, they did not arrest and continued into mitosis. They did not arrest. When wild-type cells with functioning p53 were treated with a Topo2a inhibitor, the cells arrested in G2; however, cells with mutant p53 bypassed the G2 checkpoint and entered into mitosis. This indicated that: A) the G2 decatenation checkpoint was dependent on p53 function and B) the G2 decatenation checkpoint was dysfunctional in p53 mutants and C) if the canonical (official, if you will) pathway is not functional, there must be another way they are able to progress into the cell cycle.

The researchers next wanted to look at whether proteins used in the G2 DNA Damage Checkpoint (remember, this is DIFFERENT to the G2 decatenation checkpoint) were involved in the G2 decatenation checkpoint. A loss of CHK1 or CHK2 or even both was not enough for the cancer cells to bypass the G2 decatenation checkpoint in normal cells (about as normal as a cell culture can be, so it’s not considered cancerous but its also not as normal as cells in our body seeing as the cells are living on a plate…). When cells were treated with a DNA-damaging agent called bleomycin, the cells showed CHK1 and CHK2 activation but not with ICRF193 (the Topo2a inhibitor). This shows CHK1 and CHK2 are involved with the DNA damage checkpoint but not the decatenation checkpoint. Another experiment was done to apply ICRF193 to cells and to see if there was any DNA damage and any DNA damage checkpoint activation, but there was none present. The two G2 checkpoints are distinct in nature.

After a lot of trialing and testing of different components that are related to DNA damage and repair, the study suggested that the G2 decatenation checkpoint is a non-redundant pathway consisting of the following proteins: Topo2a, SMC5/6 complex, ATM/ATR, p53 and p21. This is regulatory cascade works independently of the DNA damage repair pathway in the G2 DNA damage checkpoint.

Lockwood et al looked at S phase involvement, they induced replicative stress to see if Topo2a-dependent G2 arrest would occur, but there was none, which indicates that replicative stress during DNA replication does not impact the G2 decatenation checkpoint either. They did find that there was a delay in S phase (the DNA replication phase of the cell cycle) after 4 hours, though, when a Topo2a inhibitor was applied. In total, it was found that S phase is delayed and there is under-replicated DNA when Topo2a is inhibited but this issue did not lead to any S phase checkpoint or Topo2a-dependent G2 arrest; these issues progressed into mitosis.

Another route that the study went down was to look at PKCe, which is protein kinase C epsilon; the researchers stated that they previously found PKCe involvement in genome protection in cell lines with a defective Topo2a-dependent G2 decatenation checkpoint. Application of a Topo2a inhibitor with a PKCe inhibitor led to increased binucleated cells (2 nuclei, 1 cell) ONLY in p53-mutant cell lines. They subsequently looked at whether p53 loss was related or dependent to PKCe presence with regard to the G2 decatenation checkpoint. A loss of both p53 and PKCe in mice led to lymphoblastoma development to occur earlier than cells with p53 loss but PKCe presence. They concluded there might be a dependence between PKCe and p53.

Lockwood’s study concludes that there may be a failsafe pathway involving PKCe in which p53-mutant cells bypass the Topo2a-dependent G2 decatenation checkpoint. The study found that a PKCe signalling pathway is active when the cells enter mitosis with tangled DNA as a consequence of a loss in p53 or p21. Lockwood et al. shows evidence that there is an alternative pathway when p53 is dysfunctional, and that PKCe is involved early on in this secondary pathway. If the canonical checkpoint is not functional, p53-mutant cancer cells are able to utilise an alternative biochemical pathway in which they can continue and delay entry in the cell cycle to allow time to resolve tangled DNA. Very little is known about this pathway.

If this is a pathway that cancer cells take alternatively to the G2 decatenation checkpoint, it could provide a therapeutic advantage; we can target a pathway that only cancer cells use, potentially even removing any impact on cancer patients’ normal cells at all! Modern chemotherapy used today is very lethal to normal cells as they target pathways that all cells (not just the cancer) utlitise. It’s why someone with chemotherapy will lose all their hair – their cells literally are being stopped in their tracks or being killed by the medicine.

Main Message

The conclusion and main point of this study is that some cancer cell lines have been able to evade arrest/cell death by bypassing the G2 decatenation checkpoint that is dependent on Topo2a. The conclusions are as follows:

- p53 wildtype cell lines arrest at G2 when Topo2a inhibitors are applied but p53-mutant cell lines do not.

- This checkpoint depends on p53 and p21 fidelity

- The p53 mutant cell lines must find another pathway to continue replicating

- This G2 decatenation checkpoint is different to the G2 DNA damage checkpoint

- The G2 decatenation checkpoint is a non-redundant pathway consisting of the following proteins: Topo2a, SMC5/6 complex, ATM/ATR, p53 and p21 independent of the G2 DNA damage pathway

- Replicative stress does not induce Topo2a-dependent G2 checkpoint arrest

- Topo2a inhibition resulted in S phase delay and underreplication of DNA but no S phase checkpoint arrest or G2 decatenation checkpoint arrest, allowing mistakes to progress in mitosis.

- PKCe has been involved in genome protection previously

- PKCe loss and p53 loss in mice resulted in faster tumour growth than PKCe presence and p53 loss in mice.

- There is an interdependence in p53 and PKCe.

- PKCe may be involved in the G2 decatenation checkpoint

- There must be an alternative pathway that p53-mutant cancer cells take in order to continue in mitosis.

- PKCe must be involved early on in this alternative pathway.

- This can provide a potential therapeutic advantage by targeting a pathway only cancers take.

My Thoughts

Fascinating read. If you like primary literature, I recommend reading this one.

Similarly to Fugger’s study that I’ve covered in my last post (again, link here), there is great potential here. Both the nucleotide study and this G2 decatenation checkpoint study provide brand new untouched areas of cancer research. There is so much to find out! It’s intriguing.

Investigating an exclusive cancer-only pathway in which they cheat Topo2a inhibition can provide great insight into why medications may not be working for patients. If they have a whole different pathway up their sleeves, they can just switch between the canonical pathway and the alternative one. If we can establish all the proteins and processes in this pathway, we can identify new players that we can specifically target.

Questions to think about (no matter how stupid they could be, I always ask):

- Is it specific cancers that have this alternative pathway?

- Is this alternative pathway commonly used? It would be nice to see a large-scale study looking at this in patients rather than just in cell lines in vitro.

- Are there different types of G2 decatenation checkpoints? Who’s to say there will be only one alternative pathway? Cancer cells are highly unstable with a lot of genomic instability varying between cells even in the same tumour, could this be similar in terms of machinery?

- How does genomic instability impact the fidelity of the G2 decatenation checkpoint?

- How does genomic instability impact the alternative pathway?

- Could there be a discrepancy of the alternative pathway between different cells, different tumours, different cancers, or different people?

- Maybe there could be a general list of proteins involved in bypassing the G2 decatenation checkpoint, including PKCe, but slight differences between different cancers?

- My own study found that 1 immortalised “normal” epithelial breast cell line as well as 5 breast cancer cell lines all bypassed the G2 decatenation checkpoint, regardless of being p53 mutant or wild-type. What could be the reason for this?

- Could this be an adaptation to in vitro cell cultures exposed to Topo2a inhibition instead of being applicable to cancers in patients?

- The cell lines I worked with were all taken from human samples – what could be the demographic factor involved in the fidelity? Could ethnicity or age or gender be involved?

- What foods did they eat, what did they do, did they exercise – What could be the environmental impact on the cancer’s reaction/impact in the G2 decatenation checkpoint?

- Could previous exposure to chemotherapy have an impact/a role to the fidelity of the G2 decatenation checkpoint?

- Could MDM2, the upstream p53 regulator, impact the fidelity of the G2 decatenation checkpoint?

Lots to think about, people!

Keep thinking, and keep babbling.

References

- Barnum, K. J. & O’Connell, M J. (2014). Cell Cycle Regulation by Checkpoints. Methods Mol Biol., [online] 1170, 29-40. Available at: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4990352/pdf/nihms734418.pdf.

- Fantes, P. A. (1977). Control of Cell Size and Cycle Time in Schizosaccharomyces pombe. J. Cell Sci., [online] 24, 51-57. Available at: https://cob.silverchair-cdn.com/cob/content_public/journal/jcs/24/1/10.1242_jcs.24.1.51/1/51.pdf?Expires=1672327189&Signature=CZe6~tyUqP9Sz0C~kOeog3PhTRcp8DD2QBcgNBTPNTineQCAeU2BPu1Qvo2muY1ksSBgNVJEH60H1iou70aykWWAMn5j7hlMkXq7VQAvQuQ5EiIjHWJXy90M2s73QerJIzJtYnQxQvgdb5dTv2nhn5vhSJJx4JoyLXXbQ0hBDYlRwkzwjuWDbq4CpbwbtAYRmzxdVkjtCXm~QTDPdJrh4dBEVELAp8BNoMqpWLN90BJLPc8-ivt3RIIGtzb3XN9LRniSPeolr4Onty79s3~i0VtMz23v9P80FG4if5tke2gwQ-n7N8bIj7-a98mNJ9xpcKfIEU2eF76ekI6op35YHA__&Key-Pair-Id=APKAIE5G5CRDK6RD3PGA.

- Killander D, & Zetterberg, A. (1965). Quantitative cytochemical studies on interphase growth. I. Determination of DNA, RNA and mass content of age determined mouse fibroblasts in vitro and of intercellular variation in generation time. Exp Cell Res, [online] 38, 272–284. Available at: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/14284508/.

- Lockwood, N., Martini, S., Lopez-Pardo, A., Deiss, K., Segeren, H. A., Semple, R. K., Collins, I., Repana, D., Cobbaut, M., Soliman, T. N., Ciccarelli, F., & Parker, P.J. (2022). Genome-Protective Topoisomerase 2a-Dependent G2 Arrest Requires p53 in hTERT-Positive Cancer Cells. Cancer Research, [online] 82, 1762-1773. Available at: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/35247890/.

- Watt, P. M., & Hickson, I. D. (1994). Structure and function of type II DNA topoisomerases. Biochemical Journal, [online] 303, 681-695. Available at: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC1137600/?page=4.

Leave a reply to Son of a PICH! The Role of This ATPase in Triple Negative Breast Cancer. – Biological Babble Cancel reply